By Tim Snow | Photos Courtesy of the Lake of the Ozarks Community Bridge, george denny photography © & Con-Dev Concrete

For more intriguing stories from the 2024 LOTO RACE GUIDE, click here!

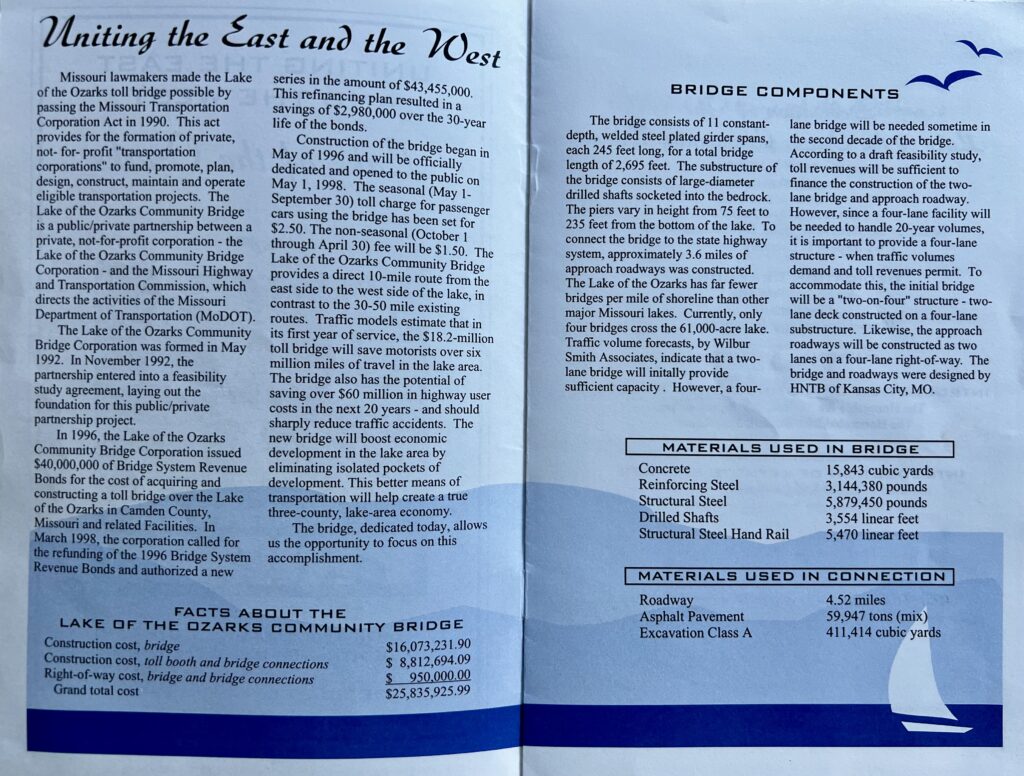

This year, as April drew to its end, so did an era at the Lake of the Ozarks. For the past twenty-six years, residents and visitors alike have paid a toll to cross the bridge from the East “St. Louis Side” of the lake to the “Kansas City Side” on the West. Officially, this bridge is known as the Lake of the Ozarks Community Bridge, but over the past decade and a half, it has been more commonly referred to as the “Toll Bridge.” Aptly named on both fronts, this particular bridge is well known for being essential to the lake community, borne of an initiative by the lake’s own residents to ease overland travel around Camden County and beyond.

Prior to construction of the Lake of the Ozarks Community Bridge, lake residents in communities like Sunrise Beach and surrounding areas were subject to incredible commutes when trying to get to the East side of the lake. The solution, building a bridge to connect both sides of the lake right in the middle, was just as clear as the problem. For a long time at the lake, it seemed like building such a convenient bridge would be impossible, and over the years, residents had been holding meetings to discuss the possibility of building a bridge that would connect Highway 5 to Highway 54, always coming up with the same conclusion; there simply weren’t any funds available for the project.

In the late 1980s, Joseph Jaeger, a legislative consultant, Joseph Roeger of First Title Insurance Co. and Warren Donaldson, an attorney, met with the Missouri Highway & Transportation Commission (MHTC) to explore different concepts available to build the bridge, reviewing and analyzing similar projects that had been built in other states. One of the concepts discussed was the formation of a transportation development district or corporation to steward a quasi-public toll bridge, one that would use toll revenue collected from bridge traffic to effectively pay for itself, in a process known as a public-private partnership.

Legislation had not yet been passed in Missouri allowing for such corporations to exist, so Jaeger, Roeger, and Donaldson, in cooperation with the MHTC, proceeded to work towards a change in the law. MoDOT undertook private initiative legislation, and though it took a few years, in 1990 a revised proposal for Public-Private Transportation Law was submitted and the Missouri General Assembly passed the MO Transportation Corporation Act, finally authorizing a privately owned toll bridge.

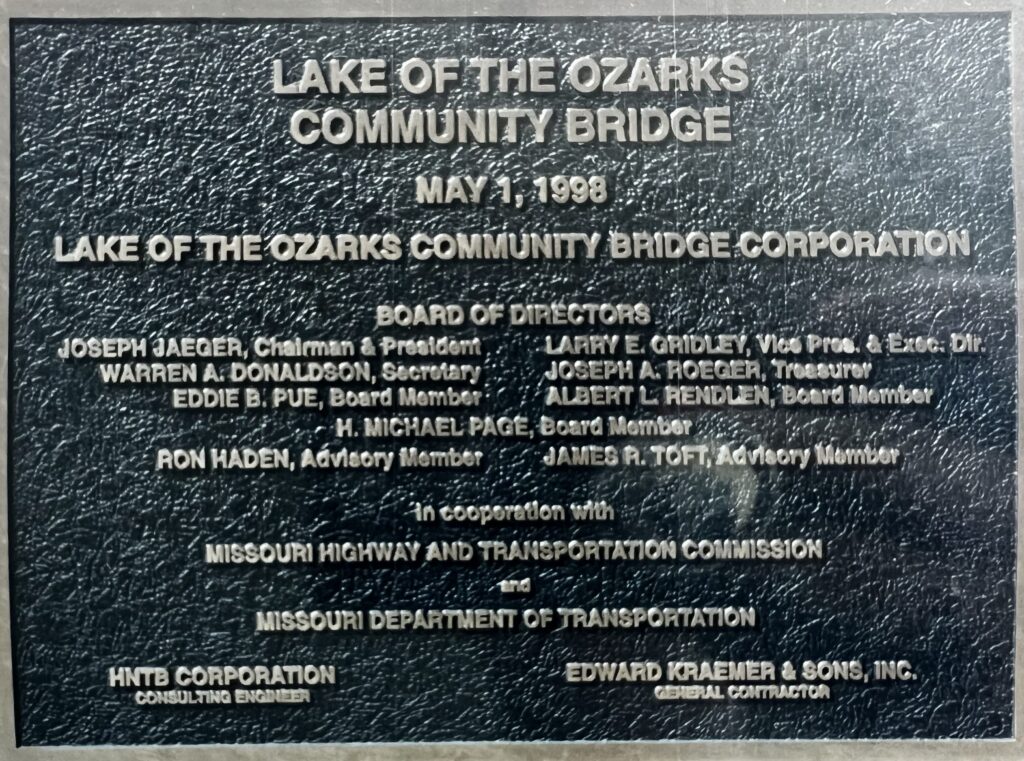

With the law on their side at last, Jaeger, Roeger and Donaldson filed an application with the MHTC for the formation of the very first transportation corporation. Their application was approved April 2, 1992, and by the first of May that very same year, the Lake of the Ozarks Community Bridge Corporation (LOCBC) was formed, which included Jaeger, Roeger, and Donaldson, but saw the addition of Eddie Pue, a realtor, Dave Krehbiel, who was at the time the Camden County Commissioner, Albert Rendlen, a retired Missouri judge, as well as Lake of the Ozarks Administrator Rick Eckert. All nominations were approved and the LOCBC’s first board of directors was established. By May 12th, a Certificate of Incorporation was issued by the MO Secretary of State, cementing the LOCBC’s status as an official entity.

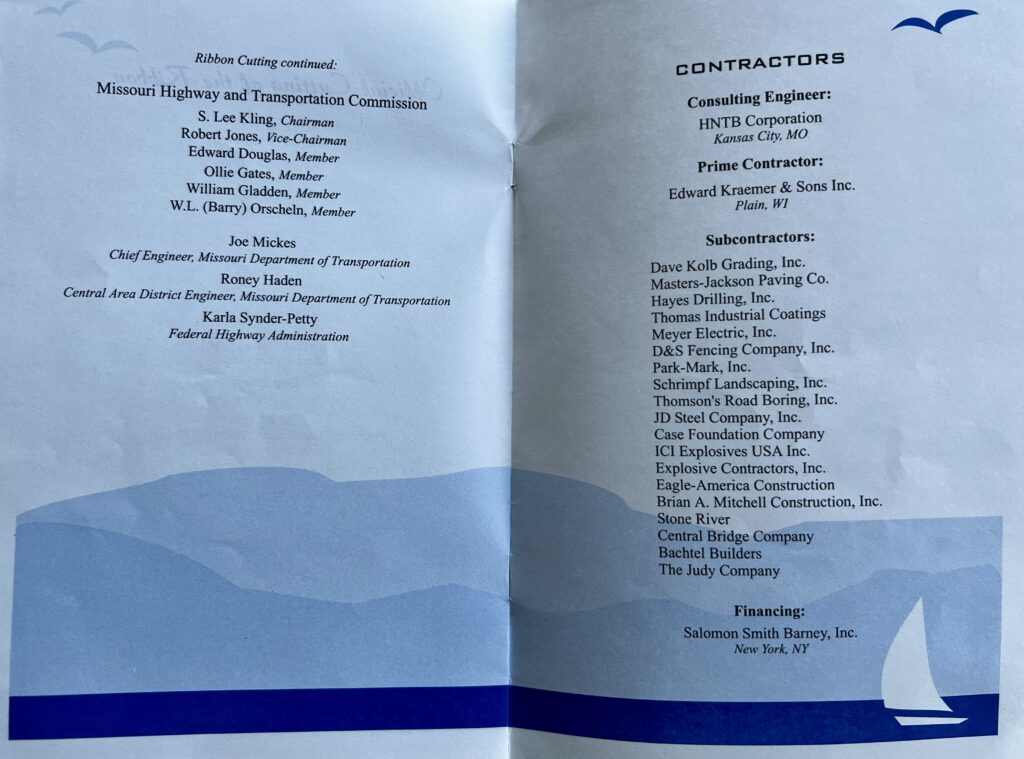

Corporate counsel, bond counsel, and engineering consultation were all required at this point, so the LOCBC set to work, hiring firms under the agreement that they would work without pay until financing became available–if it ever did. The unique opportunity to write a new chapter in Missouri history was enough motivation, and HNTB Corporation of Kansas City began work on designing the bridge. In November of 1993, the Bridge Corporation hired what was then known as Morgan Stanley Smith Barney to sell revenue bonds, financing the bridge.

A year later in November of 1994, the LOCBC executed a corporate agreement between the LOCBC and the MHTD for construction of the bridge, with MHTD having final say in bridge design and construction approval. It was agreed upon that when the toll revenue had paid for the bridge in its entirety, it would be donated freely to the MHTD (today’s MoDOT). HNTB’s final design plans were approved by the fall of 1995, a half-mile-long bridge of two lanes on a four-lane pier structure. Bids on construction were opened, and a contract was awarded to Edward Kraemer & Sons, Inc. (now known as Kraemer North America) of Plain, WI, for $23,651,925.89, a full 11% below estimated cost, with included approach ways.

While the project was a long time ago at this point, Kraemer North America, LLC.’s Upper Midwest Vice President Bob Beckel could still recall the Community Bridge project.

“Many of those who were directly involved with the project have since retired or passed away,” explained Bob. “I did work for Kraemer at the time, however, and something I recall vividly was the challenging depths of the Lake of the Ozarks as compared to other jobs of ours at that time. Normally with floating jobs, we have what are called spuds, or piles which anchor our barges to the river or lake’s bottom, but because of the sheer depths of the Lake of the Ozarks, we had to develop a different form of an anchoring system for our barges.”

When asked how Edward Kraemer & Sons, Inc., of the Village of Plain, Wisconsin—a town of less than 1,000 people in the 2022 census—landed the job of building a community toll bridge in Central Missouri in the 1990s, Bob’s answer was both quick and to the point.

“I believe we were one of multiple contractors who were invited to bid on this project, and we were the successful low bidder,” stated Bob.

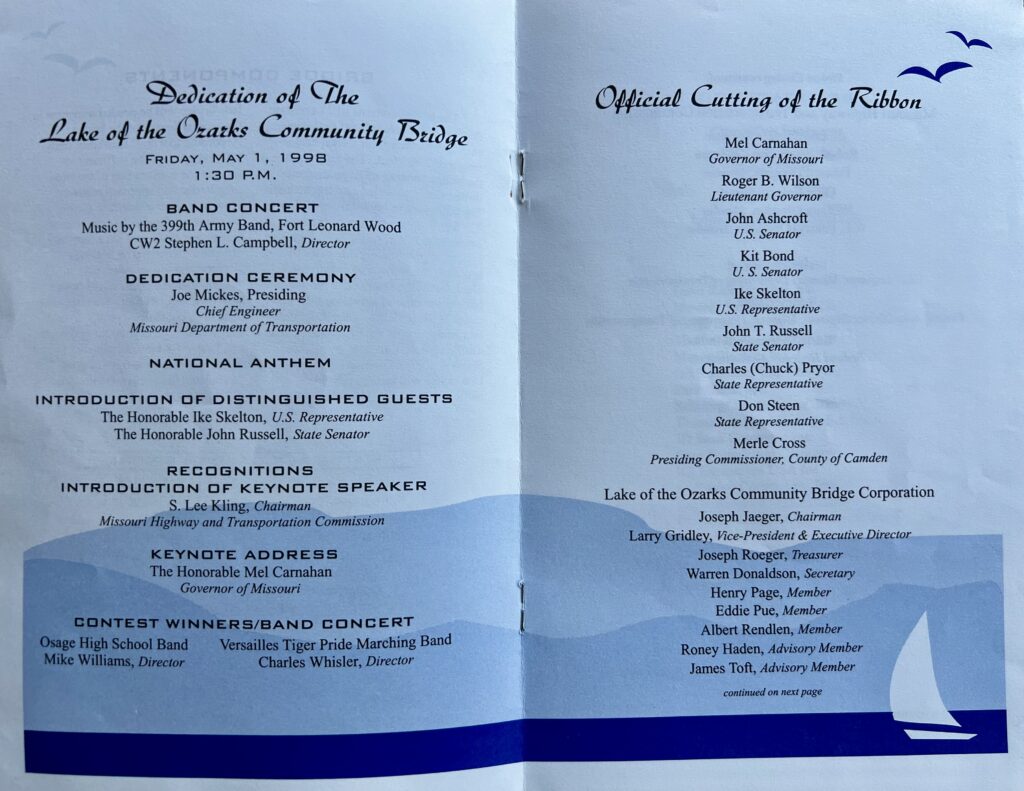

Working with local company Con-Dev Concrete Construction & Pump Service of Eldon, Missouri, led by Founder Joe Albertson, waterproof formwork was pumped out so concrete could be placed in the dry for the bridge pilings and caps. At this point, girders were erected, and the concrete deck was placed, and by May 1st, 1998, the bridge opened, alongside a ceremony that included current MO Governor Mel Carnahan, Lieutenant Governor Roger B. Wilson, U.S. Senators John Ashcroft and Kit Bond, Representative Ike Skelton, and many others.

While the toll bridge that we know today is the Lake of the Ozarks’ shining example of what a properly managed public-private partnership can do, it’s far from the only example in our nation. Public-private partnership initiatives are a way for any well-enough-organized communities to accomplish large scale government projects such as roads, hospitals or bridges utilizing private funding, as well as other means. Oftentimes, this avenue gets utilized when a project would otherwise take an exorbitantly long time to construct or would otherwise not get built at all.

Construction costs funded by the issuance of toll revenue bonds meant that the new bridge would come with a toll required to cross it, but also with the promise that when sufficient funds had been collected, the ownership of the bridge would transfer from what is now known as the Community Bridge TDD (the LOCBC was renamed Lake of the Ozarks Community Bridge Transportation Development District in 2012) to the state, and the bridge would become toll-free. Initial estimates on when the toll would be dissolved were originally set for 2026. On February 12th, 2024, however, Community Bridge TDD issued a press release announcing their intent to terminate toll collection on the bridge, a full two years early.

Toll bridges and roads in the United States are plentiful, but seeing a promise of toll removal come to fruition is not. Toll roads have been around for almost all recorded history, with the earliest mentions of tolls being collected from travelers using the Susa-Babylon highway under the rule of Assyrian king Ashurbanipal around 650 BC. With 2,700 years of tradition, having to pay a little extra to take the fastest and easiest route seems rather commonplace. In a modern democracy, however, tolls can’t just be charged without reason for use of public roadways. Or can they?

Tolls roads and bridges in the United States have been around since the founding of our country, the first of which being the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike, chartered and constructed in Pennsylvania in 1792. Interestingly, the word turnpike, which is used mostly in the Eastern United States, was first coined in the mid-1400s, referring to a spiked barrier that restricted access to certain roads, with spiky pikes installed on the tips of the barrier with the intent to turn away unwanted traffic. By the time of the building of the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike, the term had evolved to refer to the horizontal pole that barred access to toll roads, and after a few generations, the term began to refer to the toll road itself.

Initiatives put forth by both the public and the state come in waves, as roads are either built anew or maintained, then worn down again over time. Throughout our nation’s history, the funding for such projects has varied in its sources. As the nation began to industrialize in the mid-19th century, prior to the invention of the automobile, bicycling became a popular method of travel, while at the same time, rural farmers began to demand higher quality roads, as rural travel was still expensive and heavily dependent upon the weather, and existing roads were reduced to muddy ruts in the rain and produced significant amounts of dust in warmer, drier seasons.

Coalitions between farmers’ advocacy groups and bicyclist organizations provided the united public pressure necessary to turn these local complaints into a national outcry, and so the Good Roads Movement was born.

Not dissimilar to the Lake of the Ozarks Community Bridge, proponents of the Good Roads Movement saw a transportation problem and came together to fix it. Magazines were published, highlighting the need for better road systems as well as the public benefits. Farmers looking to receive mail and packages from the United States Post Office’s newly formed Rural Free Delivery service also ran into issues when the postal service made determinations on which roads were suitable for delivery and which were not. Faced with a mishmash of roads in varying states of disrepair, states began to pass legislation allowing for government participation in road-building projects.

The next few decades saw intermittent growth, as the automobile overtook the bicycle and the need for good, paved road systems grew deeper. At the outset of the world wars, the public’s demand for good road access was bolstered by a defense need to have a nation-wide highway system created to allow for the nation’s armed forces to move smoothly and uniformly around. Congress passed the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, followed by the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921, and crescendoed with President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s proposal which led to the establishment of a uniformly maintained interstate highway system with the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, funding the construction of 41,000 miles of interstate highway over a 10-year period.

Under this plan, the United States Government would pay for 90% of construction costs, diverting funds from defense spending, and individual states would be held responsible for contributing the remaining 10%. Originally, funding for these new road systems was to be provided by taxes placed on automobiles, tires, and fuel, though funds from fuel taxes proved to be the most plentiful. Many of the country’s pre-existing toll highways were incorporated into the new interstate system, and these tollways were expanded under this act with the promise that once the roads were completed, the tolls would be phased out.

Over the following decades, however, this 12-year, 25-billion-dollar plan ballooned into a 35-year, 114-billion-dollar plan.

Reasons for this inflated budget and timeframe are both varied and speculative, but by the time the Interstate Highway System proclaimed its completion in 1992 with the opening of I-70 through Glenwood Canyon in Colorado, the interstate system had grown into a massive program, and despite pledges to discontinue toll collection, many toll highways and turnpikes throughout the United States continued to collect tolls, and still do today, under the auspices that the funds will go toward maintenance of the highways and payment of toll workers. In the early millennium, the advent of Electronic Toll Collection eased traffic slowdowns due to lines at toll booths, streamlining the toll collection process while at the same time reducing operating costs, and tollways began to be seen as sources of revenue for states.

While this could easily have been the future for the Lake of the Ozarks Community Bridge, a promise made turned out to be a promise kept. A joint venture between the Lake of the Ozarks Community Bridge Corporation and MoDOT, funds were gathered through the issuance of tax-exempt toll revenue bonds. Since the construction of the bridge and the enactment of the toll, an estimated 35 million vehicles have crossed from one side of the lake to another with ease, but this year, for the first time, vehicles will be crossing it free of charge. A shining beacon of the good that a properly managed public-private partnership can do, the Lake of the Ozarks Community Bridge will now fall under the care of the Missouri Department of Transportation and will continue to facilitate smooth and stress-free travel in the lake area for years and years to come.

Current executive director, secretary, board member, and project manager for the Lake of the Ozarks Community Bridge Transportation Development District, Jim Werner, has been around for almost the full life of the bridge.

“I have been involved with the Lake of the Ozarks Community Bridge for 26 years—since February of 1998—and the bridge was opened on May 1st,” explained Jim. “There was snow on the ground, and I had my earmuffs, gloves, and coat on, but we made sure we had our cameras, IT equipment, and everything else taken care of in anticipation of our commencement ceremony and the opening of the bridge to the public that Spring.”

Lots of lessons and methods for providing for the community in smart ways have been learned over the lifespan of the Lake of the Ozarks Community Bridge TDD, and these weren’t lost on Werner.

“When we first received our bonds, we were given a very high interest rate for our 40-million-dollar project,” Werner mused. “The group of individuals overseeing this feat were smart enough to refinance the loan when the interest rates dropped. This, in addition to the uses that this bridge has allowed for, such as Co-Mo Electric, Summit Natural Gas, and Charter requesting easements to run lines across the bridge to West Side customers, have helped our community economically. The amount of good that this bridge has allowed for regarding the tax base around the Lake of the Ozarks community, in addition to an increase in business activity, household growth, and any kind of development, is why we built this bridge.”

Looking into the future, the building that houses the LOCB’s team will soon be dedicated to the Missouri Department of Transportation.

“In the coming months, MoDOT will be taking over our building as a final settlement,” Werner said, in closing. “We will continue to occupy the building throughout summer to take care of final expenses and file or dispose of all records housed there. In the Fall, MoDOT will likely come in and dispose of the toll plaza portion in the roadway and the bridge’s journey of construction and payoff will have come full circle.

Well-loved by the stewards of the project, the bridge is also well-loved by the community it was built for. Looking back on the Lake of the Ozarks Community Bridge’s legacy, and his own small part in it, Con-Dev Concrete Founder Joe Albertson found himself wistful.

“It certainly was an interesting job, and it gives me a sense of pride every time I cross it,” Joe states, albeit with one crucial consideration. “I haven’t crossed it since it became free on the 30th. I might have to make a special trip!”